By Dr Fiona McMillian

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. One of the major causes of SCC is sun exposure, which can cause DNA damage. SCC is treatable if caught early, but if left untreated for too long, it can become malignant.

Dr James Wells, research leader at The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute (UQDI), identified changes in immune cell populations during the development of SCC. The finding sheds more light on the intricate interactions between skin cancer and the immune system. The research is now published online in the journal PloS One.

Dr Wells wanted to know what role the immune system plays in the development of SCC. He has long suspected that this role changes as the disease progresses from sun-damaged skin to pre-cancerous lesions to full blown tumours.

“When you add an immunomodulating cream to pre-cancerous lesions, they disappear,” says Wells.

“But this doesn’t happen when you add it to full blown SCC.”

“There is a clear immunological difference between pre-cancerous lesions and cancerous lesions.”

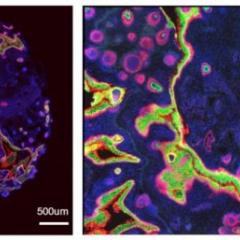

But until now, no one knew what the immune cell profile looks like as the disease develops. To find out, Wells teamed up with UQDI’s Professor Ian Frazer and Dr Fiona Simpson. Together they worked with clinicians from the Pindara Private Hospital, and scientists from the Dermatology Research Centre at UQ to determine precisely which immune cell types are found at the site of sun-damaged skin, pre-cancerous lesions, and SCC tumours.

One theory had suggested that SCC attracts a higher population of immune cells called "T regs". These cells are known for their ability to turn off an immune reaction, and given that the immune system tends to ignore SCC tumours, it was thought there must be more of them.

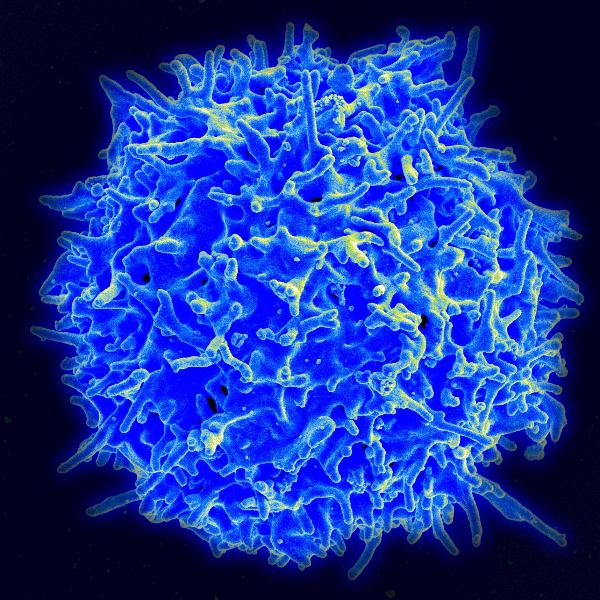

However, Wells and his colleagues discovered that SCC doesn’t attract more T regs than normal. Instead they found very clear changes in two other types of immune cells: CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells.

“CD8+ T cells are the type of immune cell that can directly recognise and destroy a tumour,” explains Wells.

He found a decrease in the number of CD8+ T cells in SCC tumours compared to pre-cancerous lesions.

“Fewer of them means a reduced capacity to attack a tumour.”

In addition, Wells and his colleagues found that SCC was associated with an increase in CD4+ T cells. The implication of this was less clear. Normally, CD4+ T cells act as ‘helper’ cells that promote an immune response, though they usually don’t destroy anything directly.

Wells wants to find out why having more of them around an SCC tumour works in the tumour’s favour. He suspects that while there may be more of them, their function has changed.

One thing is definitely clear, “We are now sure we should be looking at T cells.”

Wells has already started further collaborations to look at these subsets of T-cells, particularly those involved in immune memory.

Media: UQDI Communications Manager Kate Templeman, +61 7 3443 7027 or 0409 916 801, k.templeman@uq.edu.au.